For Ritah Asiimwe, Badminton is Joy Despite Conflict of Left and Right

Ever so often, the right side of Ritah Asiimwe’s body tries to reclaim its natural, dominant role. The right arm, instinctively, reaches out for any task. But then, she says, the left has to remind it – that without the right hand that was once there, their roles have to switch. Thought has to override instinct.

Asiimwe, like most people worldwide, was born right-handed. Growing up, she was fond of sports such as volleyball, table tennis and running.

It all changed on a day in January 2005 when she was assaulted. She woke up in hospital, weak from loss of blood, her right hand missing.

She decided, then and there, that she wouldn’t allow the catastrophe to hold her back.

“From the day I woke up, I said I never want to see myself taken to be too vulnerable. I want to be an independent person, I want to be a person making my own decisions, with my own will, so I never let the depression of losing a hand take over,” says the 35-year-old, who’s competing in women’s singles SU5 at the Tokyo Paralympics.

“It was on January 4th that I was assaulted. When I woke up in hospital I realised I didn’t have a hand anymore, (but) I need to finish my school. In February I went back home, and in March I went back to school. I wanted to complete my studies. I never wanted to see myself left behind because of what happened. I wanted to finish everything. I never wanted to see anyone look down on me or feel pity for me, I wanted to fight my challenges.”

Having lost her dominant hand, the first major challenge was to train her left hand; she had to learn to write and do the things that the right was accustomed to doing.

“I started training my left hand when I was in hospital. I had to train my left hand from scratch. I was like a baby in kindergarten, trying to write A, B, C. My teachers said I can’t finish high school because I had to learn to write. I had to catch up. I couldn’t sit for more than five minutes because my body had become so weak. I needed to keep going. I wanted to be ready, so when opportunity knocked, I had to be ready.

“I started training my left hand when I was in hospital. I had to train my left hand from scratch. I was like a baby in kindergarten, trying to write A, B, C. My teachers said I can’t finish high school because I had to learn to write. I had to catch up. I couldn’t sit for more than five minutes because my body had become so weak. I needed to keep going. I wanted to be ready, so when opportunity knocked, I had to be ready.

“Just like badminton knocked, and it found me ready.”

Growing up, Asiimwe had played many sports, but wasn’t familiar with badminton. She stayed active after losing her hand, keeping herself busy meeting friends, dancing, and going to the beach. Then she happened to visit the Uganda Para Badminton International in 2018 and realised that Para badminton was what she’d been looking for.

And just as she taught herself to write, she taught herself to play badminton with the non-dominant left hand.

There are peculiar challenges, though. Badminton is a sport of footwork as much as it is about strokeplay, and so she finds the right side of her body sometimes in conflict with her left. Instinct rules that the right leg or hand moves in accordance with the naturally dominant hand.

“I had to change my leg, it’s kind of annoying sometimes. Gradually I learnt to move with my left leg. Sometimes they collide. The right one always claims its position. I have to keep the left going.

“They do cooperate now. Every microsecond they need reminding. Sometimes when I have to hold something I check both hands and then I find I need the left has to take the place of the right, because the right still is more energetic, it tries to take over. But the left reminds it – no, you’re weak, so I’ve got to help you!” Assimwe laughs.

She’s managed to stay cheerful. And as she considers what Para badminton has done for her, she promises herself – she will keep going at it. After Tokyo 2020, she will aim for Paris 2024.

“It did take me a lot of time, around 14 years, until I found badminton. That’s when I found a new voice of freedom, that I can do anything… with badminton, I feel like I can manoevre and can do anything my mind wants to. I feel I have the guts to do it. I stopped thinking less negatively. So it’s keeping me positive. I know there’s a lot of setbacks and stigma, but it’s about your mindset.

“After the assault, my lifestyle had to change, coping up with the lifestyle of disability, the social way, everything had to change. It was a new life for me, and I had to step right from zero to where I am right now. I’m grateful, I think I can say it was a blessing in disguise. Right now, I feel like it was a blessing.”

Olympic and Paralympic News

Zhang & Wang: Stars With Different Legacies 4 June 2023

2021 in Review: Stories from Tokyo 30 December 2021

2021 in Review: Tokyo Olympics by Numbers 26 December 2021

Why Para Badminton Proved Irresistible 14 September 2021

Gritty Wins by Cheng, Mazur 5 September 2021

Pramod Bhagat Delivers on Promise 4 September 2021

Golden Day for Cheah Liek Hou! 4 September 2021

Lucas Mazur Wins Thriller 4 September 2021

17 Years After Paralympic Bronze, Suter-Erath in Sight of Medal 3 September 2021

Tokyo Diary: End of a Long Wait 30 August 2021

#RaiseARacket for Your Heroes These Tokyo 2020 Paralympics 24 August 2021

Tokyo 2020 Review: Enigmatic Brilliance of a Shooting Star 13 August 2021

Tokyo 2020 Review: Powered by Emotion 12 August 2021

Tokyo 2020 Review: Reclaiming the Crown 11 August 2021

Tokyo 2020 Review: Compelling, Commanding Performance 10 August 2021

Tokyo 2020 Review: Into the Limelight 9 August 2021

Tokyo 2020 in Numbers 7 August 2021

Punching Above Their Weight 6 August 2021

First-Time Nations Make Strong Impression 5 August 2021

What Keeps Them Ticking? 4 August 2021

Olympic Gold, New Shirt and Royal Favour 3 August 2021

Axelsen Scales Olympic Summit 3 August 2021

‘Just Run With Me’ 2 August 2021

Chen Reclaims Crown for China 2 August 2021

Masterclass from Chen; Lin Dan’s Record in Sight 1 August 2021

How Cordon Left Home at 12 to Chase Olympic Dream 1 August 2021

Lee/Wang Ensure Golden Day for Chinese Taipei 31 July 2021

Tai Puts On a Show 31 July 2021

Olympic Redemption after Personal Tragedy for Greysia Polii 31 July 2021

Cordon Scores a Win for the Ages 31 July 2021

Chinese Taipei Savour Special Day 30 July 2021

Challengers Upstage Favourites 30 July 2021

He Bing Jiao Outwits Okuhara; Sets Up All-China Semifinal 30 July 2021

Cordon’s Dream Run Continues 29 July 2021

Lee/Wang’s Landmark for Chinese Taipei 29 July 2021

On-Fire Malaysians Trip Indonesia’s Minions 29 July 2021

Beiwen Zhang Retires Hurt with Achilles Tendon Injury 29 July 2021

Kento Momota Crashes Out 28 July 2021

Kevin Cordon Stuns Angus 28 July 2021

Intanon Survives Scare from Soniia Cheah 28 July 2021

Win or Lose, Nguyen Wants to Do Migrant Parents Proud 28 July 2021

Hong Kong China, Japan in Semifinals 28 July 2021

Dwicahyo Ensures Azerbaijan’s Bright Debut 27 July 2021

Coelho: I Worked Five Years for This Moment 27 July 2021

Lee/Wang Outplay Minions; Australian Surprise for Danes 27 July 2021

An Iranian Experiences Her Moment of Olympic Glory 26 July 2021

Tang/Tse Clinch Thriller to Make Quarterfinals 26 July 2021

Christie Vows to Honour Late Brother’s Memory 25 July 2021

Danes Blow Group C Wide Open 25 July 2021

Emotional Okuhara Inspired by Champion Judoka 25 July 2021

Zilberman Aces Test at Praneeth’s Expense 24 July 2021

Impressive Show by Aram Mahmoud 24 July 2021

Tokyo 2020 Preview: Element of Unpredictability 23 July 2021

Tokyo 2020: Flying the Flag for Nation and Badminton 23 July 2021

Tokyo 2020: A Parliamentarian at the Olympics 22 July 2021

Tokyo 2020 Preview: Group D On Knife Edge 22 July 2021

The Fulfilment of a 10-Year Promise 21 July 2021

Tokyo 2020 Preview: The Promise of Fireworks 21 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Immortality Awaits Evergreen Setiawan 21 July 2021

Tokyo 2020 Preview: Spectacular Show on the Cards 20 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Top Seeds Who Struck Gold 20 July 2021

#RaiseARacket for Your Heroes These Tokyo 2020 Olympics 19 July 2021

Tokyo 2020 Preview: Recent Form Favours Axelsen 19 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Paved with Friendship and Inspiration 18 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Unseeded Gold Medal Winners 18 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: ‘Daddies’ Feel Relaxed Ahead of Olympics 17 July 2021

Olympic Legacies: Will the ‘Famous Eight’ Add a Ninth Member? 17 July 2021

Road To Tokyo: Bumpy Journey but No Regrets 16 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: ‘Beating Tai Tzu Ying Was Turning Point’ 16 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: For Spain and for Marin 15 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Watanabe Unfazed by Double Duty 15 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: ‘I’m Quite Stubborn’ 14 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: ‘A Chance to Show Strength’ 14 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Germans Primed for Big Push 13 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Tai Aware Errors Could Prove Costly 12 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: ‘Everyone’s in the Same Boat’ 12 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Ng’s Du-ing Just Fine 11 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: All About Keeping It Simple 10 July 2021

Road To Tokyo: ‘Not Going to Japan to Have Fun’ 9 July 2021

Tokyo 2020 Draw: Minions In Tricky Terrain 8 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Myanmar Talent Hopes to Make Impact 7 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: ‘We Want to Compete, Not Just Participate’ 6 July 2021

Tokyo 2020 Badminton Qualifiers Announced 5 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Japan Sweet Japan for Koreans 4 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: All Prepped and Ready for Battle 2 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: Shahzad Relishes Proud Moment for Pakistan Badminton 1 July 2021

Road to Tokyo: The Promise of a Big Impact 30 June 2021

Road to Tokyo: Life Only Gets Better for Axelsen the Gold Hunter 29 June 2021

Olympic Legacies: Most Medals in the Bag 27 June 2021

Road to Tokyo: Okuhara’s Evolution Since Rio 26 June 2021

Road to Tokyo: Goh Blazes Trail for Malaysia 25 June 2021

Did You Know? Ahsan’s Best Olympic Run Wasn’t With Setiawan 24 June 2021

Olympic Day: My First Olympics 23 June 2021

Sozonov’s World Outside Court: Literature, History, Music 22 June 2021

Mahmoud Hopes to Inspire Refugees Worldwide 20 June 2021

‘Top Priority is to Ensure Safe and Successful Olympics’ 17 June 2021

40 Days to Tokyo 2020: Women’s Singles Dark Horses 13 June 2021

‘During Lockdown I Was Grinding, Training Really Hard’ 11 June 2021

Destination Reached, a New Journey Begins for Mahmoud 10 June 2021

Aram Mahmoud Makes the Cut for Tokyo 2020 8 June 2021

‘It’s About Maximising What I Can Take From Tokyo’ 6 June 2021

50 Days to Tokyo 2020: Japan’s Dream – Matching Chinese Sweep of... 3 June 2021

Injured Olympic Champion Marin to Miss Tokyo 2020 1 June 2021

Updates on Tokyo 2020 Olympic Qualifying 28 May 2021

Road to Tokyo Reunites Pair Split by 900km 27 May 2021

60 Days to Tokyo 2020: Men’s Doubles Dark Horses 24 May 2021

80 Days to Tokyo 2020: Women’s Doubles Dark Horses 4 May 2021

Pan Am Championships: Debut Title for Brian Yang 3 May 2021

European Championships: Alimov/Davletova Make History 3 May 2021

Pan Am Championships: Rachel Chan Stuns Iris Wang 2 May 2021

European Championships: Lauren Smith in Sight of Double 2 May 2021

Pan Am Championships: Setback for Ygor Coelho 1 May 2021

European Championships: Russians Continue to Torment Gicquel/Delrue 1 May 2021

Pan Am Championships: Ho-Shue, Sankeerth Stretched 30 April 2021

European Championships: Good Day for Turkey 29 April 2021

European Championships: Hungry Korosi Bags Gift for Son 28 April 2021

Endo/Watanabe: Cruise Mode as Tokyo Looms Ahead 17 April 2021

COVID Turns Nguyen Match-Savvy 15 April 2021

100 Days to Tokyo 2020: Mixed Doubles Dark Horses 14 April 2021

国际奥委会批准修订版2020年东京奥运会参赛资格规则 5 March 2021

IOC Approves Revised Qualification System for Tokyo 2020 1 March 2021

IOC President Promises Athletes ‘Fantastic Experience’ 25 November 2020

Books the Ideal Mental Health Remedy for Leydon-Davis 5 November 2020

‘Small Things’ Drive Ygor Coelho Forward 3 November 2020

Lockdown Gives Lefel a Second Shot at Tokyo 27 October 2020

On This Day: When Lin and Lee First Contested an Olympic Final 17 August 2020

‘Golden Slot’ Again for Badminton at Tokyo 2020 25 July 2020

Badminton’s Most Successful Olympians 23 July 2020

Refugee Athlete Mahmoud Resilient Despite Lockdown Blues 20 June 2020

Pandemic Spurs Pak to Pick Up Sixth Language 31 May 2020

Marcus Ellis | Part II: Homing in on Success 30 May 2020

‘The Break is Nice… But It’s a Little Too Long!’ 2 May 2020

New Dates Announced for Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics 30 March 2020

BWF Responds to Tokyo 2020 Postponement 25 March 2020

Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games Postponed 24 March 2020

COVID-19 Leads to Suspension of Further Events 20 March 2020

IOC Issues Communique on Tokyo 2020 18 March 2020

‘Scarred’ Momota Dreaming of Olympic Glory Again 9 March 2020

Badminton Asia Championships Moved To Manila 4 March 2020

IOC President Confident of Successful Olympics 4 March 2020

Olympic Qualifier in Portugal Called Off 2 March 2020

‘Big Teams Are Taking Us More Seriously’ 28 February 2020

BWF Statement on Postponement of Vietnam International Challenge 25 February 2020

Countdown to Glory – Five Months to Go 25 February 2020

‘She Thought I was Joking About Pairing Up’ 19 February 2020

Bold Predictions for 2020 15 February 2020

Sindhu’s New Strength is her Presence of Mind 13 February 2020

Beyond the Numbers Game 12 February 2020

Sabrina Jaquet: Seeking Rhythm 11 February 2020

Ho-Shue: Primed for a Twin Challenge 7 February 2020

Mahmoud Hangs On Despite Challenges 3 February 2020

BWF Statement on Postponement of Lingshui China Masters 1 February 2020

Gicquel & Delrue: Rapid Ascent 30 January 2020

Thai Triumph Provides Fillip for Ellis & Smith in Olympic Year 28 January 2020

A Leap Up for Thygesen & Fruergaard 22 January 2020

Tokyo Legends Inspiring Current Stars 21 December 2019

Stoevas Seek Form After Disruption 25 November 2019

Olympic Champ Carolina Marin Returns 11 September 2019

Pan Am Champs Seek to Sharpen Skills 5 September 2019

IOC President Fascinated with Badminton Finals 29 August 2019

Miyuki Maeda Revels in New Role 9 August 2019

Olympic Fever in Tokyo 27 July 2019

One Year To Tokyo 2020: Players’ Thumbs-Up for Olympics Venue 24 July 2019

Olympic Dreams Spur On Refugee Champ Mahmoud 12 July 2019

Aram Mahmoud Receives IOC Refugee Athlete Scholarship 21 June 2019

Michelle Li – Playing with Pain on Road to Tokyo 11 June 2019

‘Competition Against Great Players Brought Out Best in Me’ – Bang Soo... 6 June 2019

What We Have Learned – Road To Tokyo 29 May 2019

Timely Reward for Christie 6 May 2019

‘Ygor’ for Success in Tokyo! 30 April 2019

And They’re Off! 29 April 2019

Fighting To Be Fit Again 28 April 2019

Badminton Olympic Competition Schedule Announced 16 April 2019

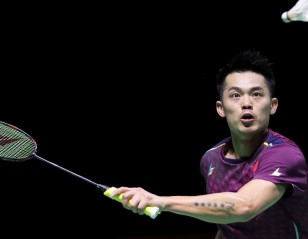

Lee Chong Wei in Search of Olympic miracle 16 April 2019

New Lustre to the Legend 10 April 2019

Tai Undecided on Retirement Post Tokyo 2020 8 April 2019

Somerville/Mapasa Seek to Cover Lost Ground 5 April 2019

Comeback Man Parupalli Targets Tokyo 2020 2 April 2019

Women Trailblazers – Rio Flashback 23 March 2019

New Era Set to Dawn – Road To Tokyo 23 March 2019

Tokyo 2020 on the Horizon 22 March 2019